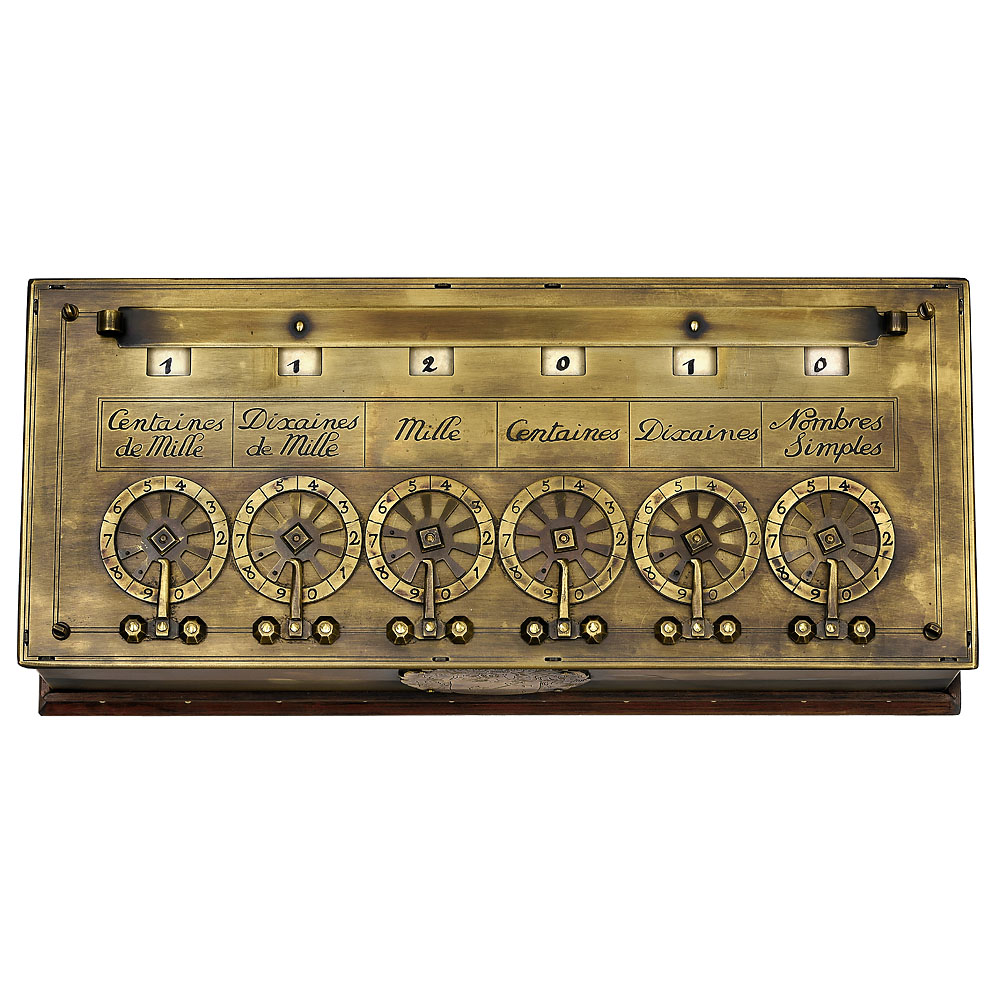

Working Replica of the Six-Digit “Pascaline Calculator” Replica

Starting bid: € 3.000 | Estimate: € 5.000 – 8.000

With lacquered-brass case, spoked digit-wheels with engraved white-metal scales corresponding (right to left) to: “Nombre Cimple”, “dixaines”, “Centaines”, “mille”, “dixaines de mille” and “Cantainnes de mille”, sliding rule for changing display from addition to subtraction, brass-framed interior mechanism with six axles each carrying three lantern gears and an inscribed paper-covered drum for the display, on wood plinth with four feet and hinged flap, width 12 in. (31,5) x depth 5 1/8 in. (13 cm) x height 3 in. (7,8 cm). Note: Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), mathematician, physicist and philosopher, is credited with the invention of the first mechanical calculator capable of addition and subtraction. His father, Étienne Pascal, was a lawyer and a judge in the tax court who assumed a new position as tax commissioner for Upper Normandy, based in Rouen, in 1639. – France had declared war with Spain four years earlier, leading the French government to renege on part of its internal debt and to increase taxation. Étienne – assisted by his son – was under pressure to keep accurate account of the rising tax levies with only the help of counting boards. In 1642 the 19-year old Blaise began designs for a machine that would simplify his father’s work. As a reviewer wrote in Le Figaro Littéraire in 1947, “the calculating machine was born of a filial love flying to the rescue of the tax man”. – Pascal’s first design was for a five-digit calculator; he later refined his principal by creating six and eight-digit machines. Due to the difficulty in cutting toothed gears accurately, Pascal used lantern-type gears formed by pinned wheels that could turn in one direction only. – His design was simultaneously simple and brilliant; the Pascaline could add and subtract two numbers directly and multiply and divide by repetition. The six digit-wheels on the outer case are connected to axles that each carry three lantern gears and a paper-covered drum with inscribed figures. The digit-wheels were rotated by a stylus. For addition, a sliding rule located on the number display was pushed upwards for digits from 0–9. For subtraction, the rule was pushed downwards for digits from 9–0. – The Pascaline was also revolutionary for including digital carry-over. Whenever a ten was carried, a ratchet mounted between the gears, pushed the adjacent gear around a notch, so that the display moved one digit higher. Unfortunately for its operator, a design flaw meant that the ratchets were inclined to jam – perhaps one reason why production of the Pascaline was not financially successful at 100 Livres apiece. It was, however, a mathematical sensation, leading Pascal’s friend, the poet Charles Vion Dalibray, to compose a sonnet in its honor: – “… Calculation was the action of a reasonable man, And: now your inimitable skill. Has given the power to the slowest of wits”. – Pascal accordingly applied for a privilege (the 17th Century term for a patent), which was only eventually granted in 1649, after its inventor had presented the issuing officer, Chancellor Seguier, with an 8-digit calculator of his own. – The total production of the Pascaline is not known, however, researchers estimate that no more than 20 examples were produced, of which 9 are known today. It was, nevertheless, an historic achievement, not least for demonstrating “that an apparently intellectual process like arithmetic could be performed by a machine”. Its introduction led to the development of mechanical calculators in Europe and, eventually, to the invention of the very first microprocessor, the “Intel 4004”, for the “Busicom 141-PF” electronic desk calculator in 1971. Understood in this way, the Pascaline is arguably world’s earliest mechanical computer. – Literature: Stan Augarten, “Bit by Bit, An Illustrated History of Computers”, 1984, pp. 22–30. – A historically accurate replica from 2011.

“Pascaline” (oder: “Arithmatique”), Replikat-Rechenmaschine von Blaise Pascal

Legendäre 1. mechanische Rechenmaschine der Welt des großen französischen Mathematikers und Philosophen, der 1623 in Clermont-Ferrand in der Auvergne geboren wurde. Bereits als Kind hatte er einige anerkannte fundamentale mathematische Lehrsätze entwickelt, zum Beispiel über geometrische Kegelschnitte. Blaise Pascal schrieb später zahlreiche mathematische Abhandlungen, er bewies die Abhängigkeit des Luftdrucks von der Höhe des jeweiligen Ortes, diskutierte die Frage des Vakuums gegen den Willen der Naturforscher und schuf die Grundlagen für die Entwicklung der Hydraulik … – heute noch gebräuchlich als “Pascal’sches Gesetz”. – Mit 19 Jahren entwickelte Blaise Pascal seine erste Rechenmaschine, nach zahlreichen zeitgenössischen Berichten sollen nur max. 20 Stück je gebaut worden sein, wovon heute noch 9 Exemplare – ausschließlich in öffentlichen Museen – bekannt sind. Aber hier nun – sensationell – die 10. Maschine (!!) … die damit die einzige auf dem freien Weltmarkt ist! – Die “Pascaline” ist für Addition sowie Subtraktion nach der Neuner- bzw. Zehner-Komplement-Methode (= addieren, um zu subtrahieren) konzipiert, da sie nur in einer Richtung gleichlaufende Zahnräder aufweist. – Zum Rechenvorgang: Dieser begann mit der Nullstellung aller Schaulöcher durch Verdrehen der Zifferräder. Zum Addieren wurde das an den Anzeigerollen befindliche Lineal nach oben geschoben. Die Anzeigerollen waren 2-reihig mit Ziffernfolgen gekennzeichnet. Die untere Reihe war nach rechtslaufend steigend von 0 bis 9 (Addition) und in der oberen Reihe fallend von 9 bis 0 (Subtraktion) ausgelegt. Für beide Rechenarten galt also die gleiche mechanische Handhabung: Ein Stift wurde in den Speichenzwischenraum der entsprechenden Ziffer des Einstellrades eingeführt und dann bis zum Anschlag herumgedreht. Zur Umschaltung von Addition auf Subtraktion wurde lediglich das Lineal nach unten geschoben. Die Arbeitsweise blieb die gleiche. Pascals Rechenmaschinen hatten von Anbeginn bereits Zehnerübertragung und konnten auch zur Multiplikation eingesetzt werden, was allerdings einem sehr mühsamen Unterfangen gleichkam. – Blaise Pascal erhielt 1649 für seine Rechenmaschine das “Royal Privilège”, und sie war damit die erste patentierte Rechenmaschine der Welt”! Außerdem war die “Pascaline” auch die erste Rechenmaschine mit automatischer Zehnerübertragung, wie sie auch die erste Rechenmaschine in Serienproduktion war. Mit Blaise Pascal und seiner Rechenmaschine begann die Entwicklung der mechanischen Rechner, zunächst in Europa und dann weltweit, was dann schließlich nach mehr als 300 Jahren zur Erfindung des ersten Mikroprozessors führte, den “Intel 4004”, der für den ersten Elektronen-Tischrechner der Welt, den “Busicom 141-PF” von 1971, entwickelt wurde. Die hier angebotene Maschine ist eine sehr originalgetreue Kopie aus dem Jahr 2011.